THE NEW YORK TIMES:

‘We Didn’t Want to Sit Idle’: A Rush to Meet Pro Sports’ Testing Needs

By James Wagner

Published: July 12, 2020

Published: July 12, 2020

By mid-April, the Food and Drug Administration granted the Rutgers lab an emergency-use authorization. A month later, it received authorization for the test kit to be used at home.

That saliva kit is now a key part of Major League Baseball’s plan to return to play and has also been used by other revived sports leagues, including the PGA Tour and Major League Soccer.

With sports leagues desperate to salvage their seasons and profits, testing was always crucial — even more so now as the number of cases rises nationwide. But there was no blueprint, so a patchwork of businesses and labs, all with entirely different missions before the pandemic, converged to meet the need.

A version of Spectrum’s spit test once used to help figure out family trees, is now spotting infections. Vault Health, a telehealth company that was focused on sexual health and weight-loss therapies for men, is now using Spectrum’s saliva kit and the Rutgers lab to help leagues conduct wide-scale testing. And the Sports Medicine Research and Testing Laboratory in Utah, which previously handled anti-doping testing for M.L.B., is now processing coronavirus saliva tests for the league.

Dr. Daniel Eichner, the president and laboratory director of SMRTL, the shorthand name for the Utah lab doing M.L.B.’s coronavirus testing, acknowledged that there was “nothing good about this virus.” But, he said, he was proud of his team’s ability to pivot to this new challenge, like other companies.

“It’s a beautiful American story: When the chips are down, people jump in to contribute as best they can,” Dr. Eichner said.

A handful of companies and labs quickly overhauled themselves to fulfill the sudden demand for coronavirus testing from the major American pro leagues.

In early March, as the coronavirus was spreading across the United States and testing capacity was already a problem, Bill Phillips had an idea.

Phillips is the chief operating officer of a medical device company, Spectrum Solutions, that provides saliva test kits for companies like Ancestry.com. He wondered if Spectrum’s kits — which require customers to spit in a tube and ship their samples through the mail — could work with detecting this new virus.

“I just threw it out there: Why don’t we test our device to see if we can use it as a transport medium to get it to the lab?” Phillips recalled in a recent telephone interview.

Spectrum, based outside Salt Lake City, teamed up with a laboratory at Rutgers University, made a few tweaks, and found that the effectiveness of their saliva test kit was comparable to the nasopharyngeal test, or the long swab, that was already in widespread use.

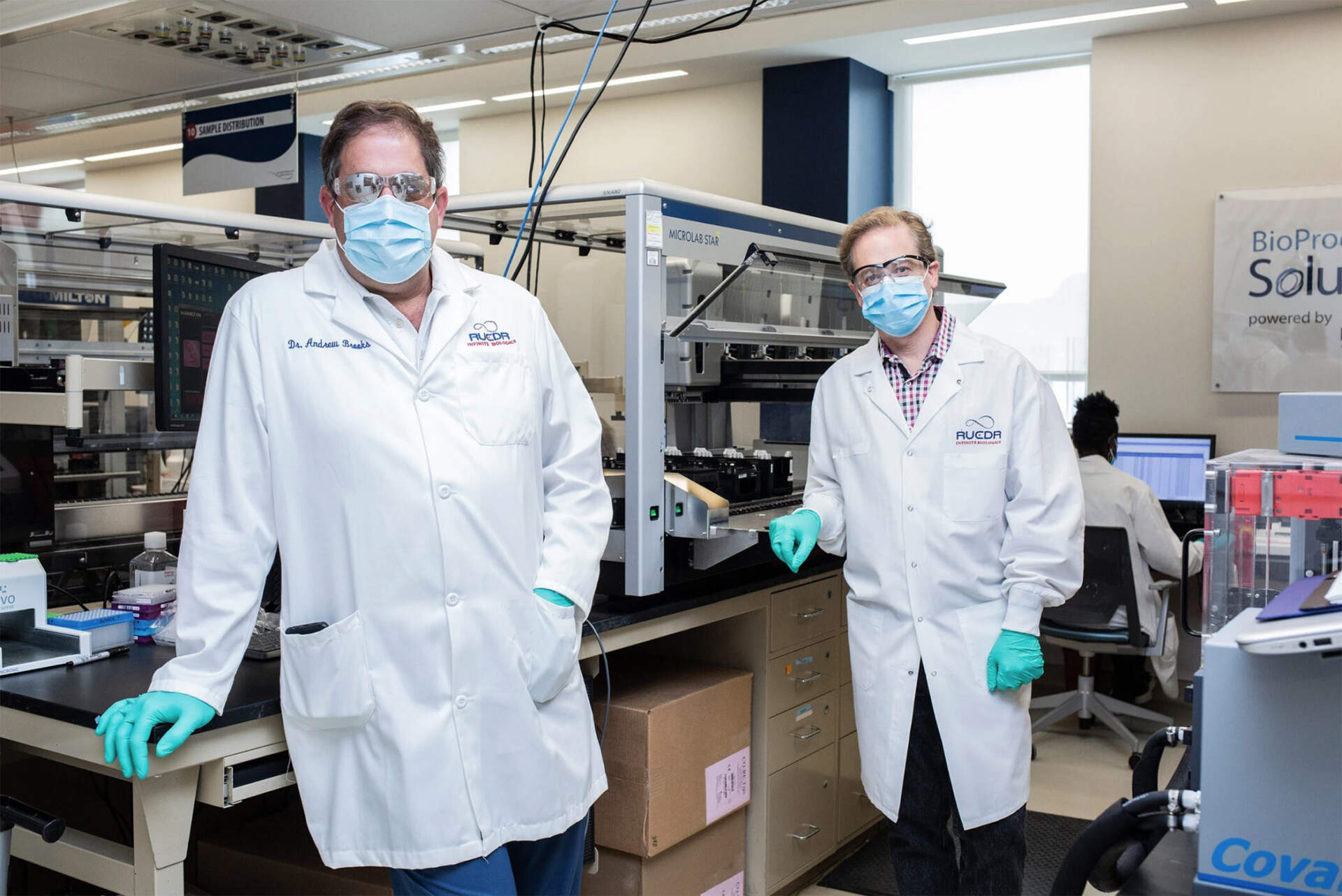

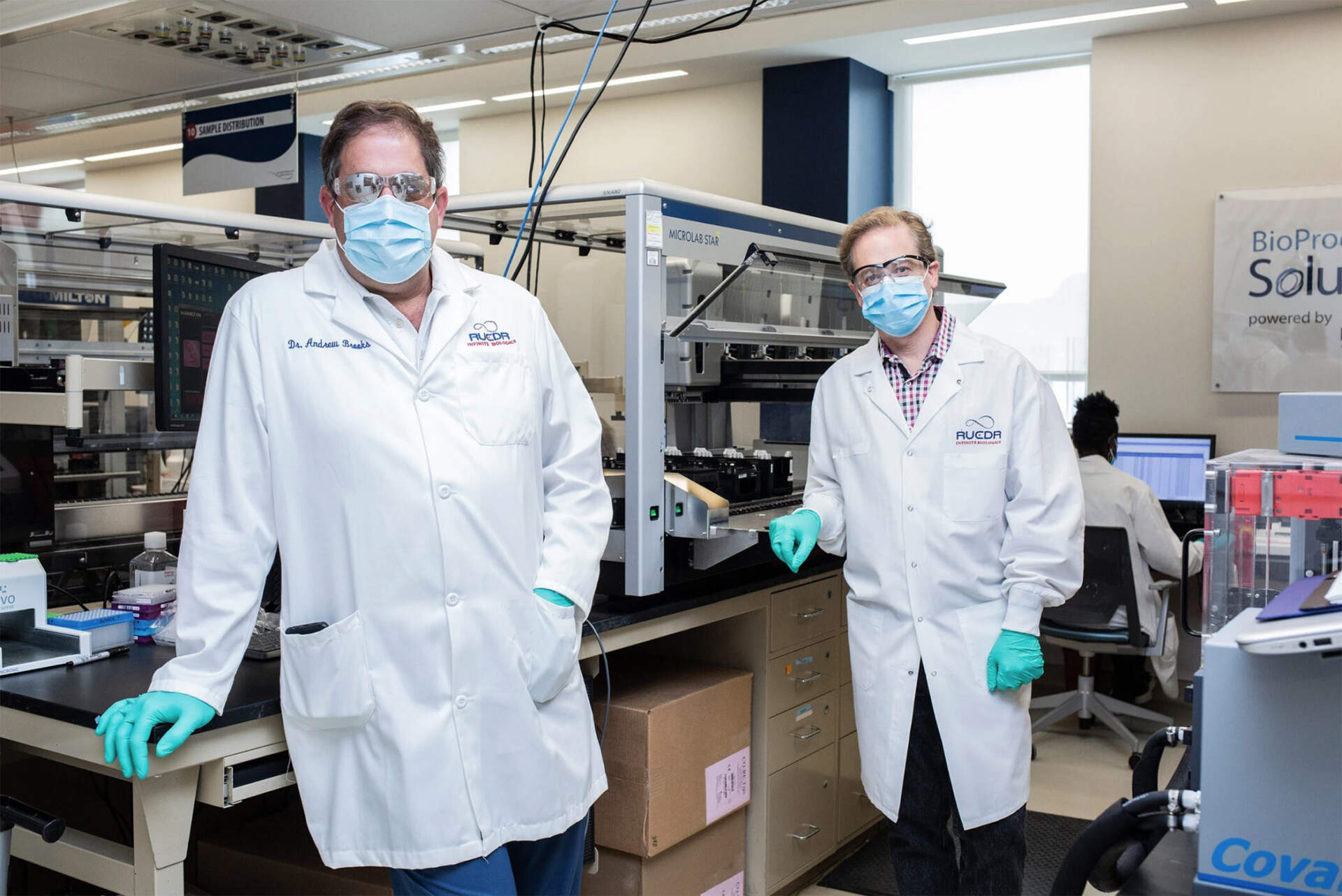

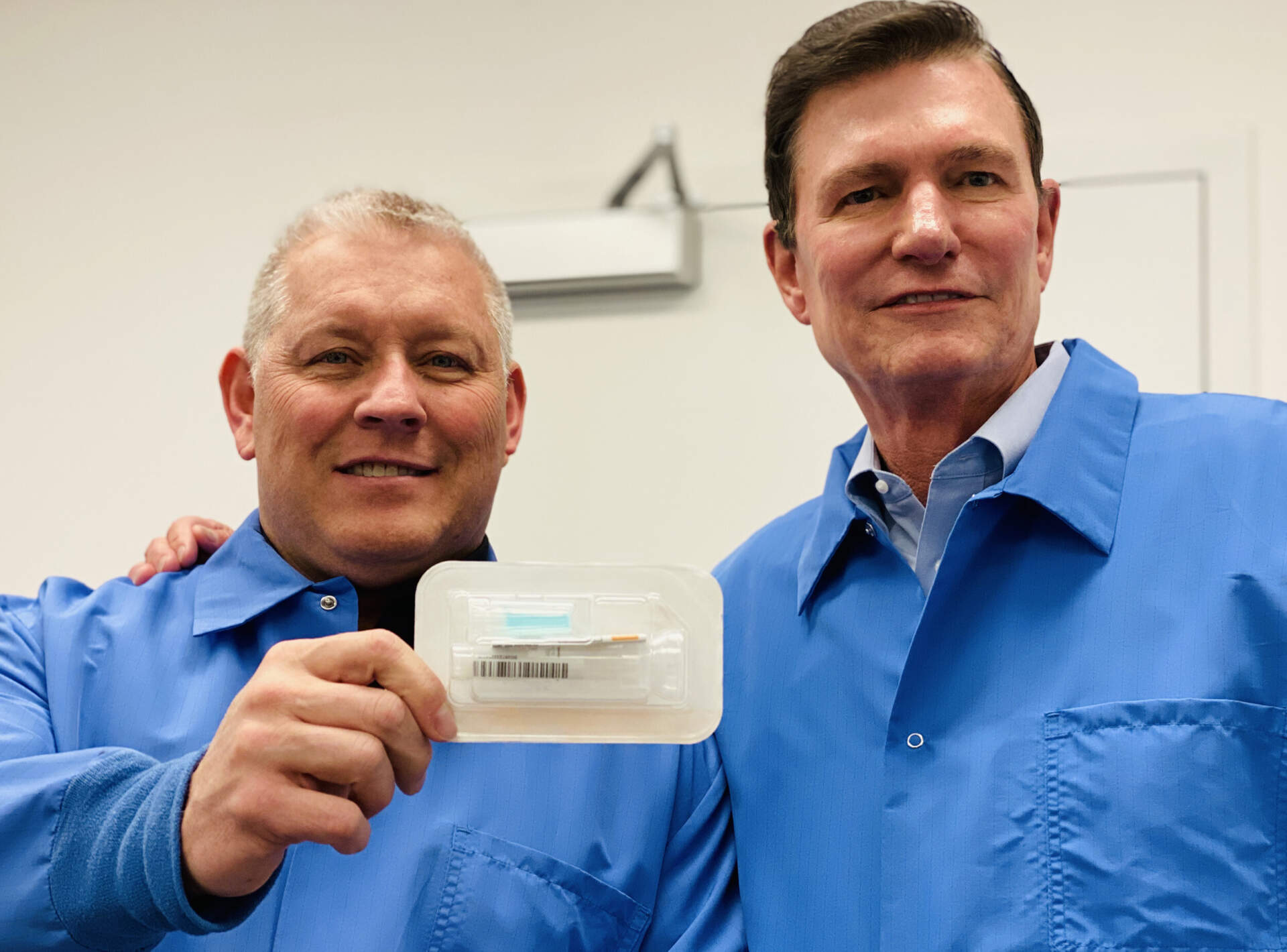

Dr. Andy Brooks, left, and Jason Feldman, right, at the RUCDR Infinite Biologics lab at Rutgers University, which has become a crucial hub for several leagues’ virus testing. Credit…Bryan Anselm for The New York Times

THE NEW YORK TIMES:

‘We Didn’t Want to Sit Idle’: A Rush to Meet Pro Sports’ Testing Needs

By James Wagner

Published: July 12, 2020

Published: July 12, 2020

By mid-April, the Food and Drug Administration granted the Rutgers lab an emergency-use authorization. A month later, it received authorization for the test kit to be used at home.

That saliva kit is now a key part of Major League Baseball’s plan to return to play and has also been used by other revived sports leagues, including the PGA Tour and Major League Soccer.

With sports leagues desperate to salvage their seasons and profits, testing was always crucial — even more so now as the number of cases rises nationwide. But there was no blueprint, so a patchwork of businesses and labs, all with entirely different missions before the pandemic, converged to meet the need.

A version of Spectrum’s spit test once used to help figure out family trees, is now spotting infections. Vault Health, a telehealth company that was focused on sexual health and weight-loss therapies for men, is now using Spectrum’s saliva kit and the Rutgers lab to help leagues conduct wide-scale testing. And the Sports Medicine Research and Testing Laboratory in Utah, which previously handled anti-doping testing for M.L.B., is now processing coronavirus saliva tests for the league.

Dr. Daniel Eichner, the president and laboratory director of SMRTL, the shorthand name for the Utah lab doing M.L.B.’s coronavirus testing, acknowledged that there was “nothing good about this virus.” But, he said, he was proud of his team’s ability to pivot to this new challenge, like other companies.

“It’s a beautiful American story: When the chips are down, people jump in to contribute as best they can,” Dr. Eichner said.

A handful of companies and labs quickly overhauled themselves to fulfill the sudden demand for coronavirus testing from the major American pro leagues.

In early March, as the coronavirus was spreading across the United States and testing capacity was already a problem, Bill Phillips had an idea.

Phillips is the chief operating officer of a medical device company, Spectrum Solutions, that provides saliva test kits for companies like Ancestry.com. He wondered if Spectrum’s kits — which require customers to spit in a tube and ship their samples through the mail — could work with detecting this new virus.

“I just threw it out there: Why don’t we test our device to see if we can use it as a transport medium to get it to the lab?” Phillips recalled in a recent telephone interview.

Spectrum, based outside Salt Lake City, teamed up with a laboratory at Rutgers University, made a few tweaks, and found that the effectiveness of their saliva test kit was comparable to the nasopharyngeal test, or the long swab, that was already in widespread use.

Dr. Andy Brooks, left, and Jason Feldman, right, at the RUCDR Infinite Biologics lab at Rutgers University, which has become a crucial hub for several leagues’ virus testing. Credit…Bryan Anselm for The New York Times

Seeing an Opportunity

Navigating the rapidly evolving world of coronavirus testing has been far from a simple task for professional sports leagues. They have had to weigh the efficacy and speed of various tests and companies, all while trying to ensure they would not be taking away resources from those who needed them more.

“It was incredibly complicated,” said Andy Levinson, the PGA Tour’s senior vice president of tournament administration.

When leagues began exploring their options — Levinson said the tour consulted laboratory directors and its own medical advisers — saliva-based tests emerged as a popular choice. They could be done almost anywhere, with minimal assistance from a medical professional and without much personal protective equipment, and some studies found saliva was a reliable alternative to the more-common nasopharyngeal swabs.

Another benefit: Spitting in a tube is much less painful than a swab shoved deep into the nasal cavity.

“We call it the brain tickler,” said Jason Feldman, the chief executive of Vault Health. Feldman’s company is now a linchpin for several leagues’ coronavirus testing operations. Before the pandemic, it was part of a growing wave of telehealth companies, connecting patients with doctors via video calls, and facilitating shipments of treatments through the mail.

When the pandemic hit the U.S., Feldman, like many business owners, feared the potential economic effects on his company. But then he realized he was sitting on a wealth of resources that would be useful amid the crisis: He had a relationship with both the Rutgers lab, known as RUCDR Infinite Biologics, and Spectrum Solutions for other products, and a virtual consultation platform that would provide a safe way to talk to patients.

Vault Health devised an at-home saliva testing package, which is supervised via a Zoom video call and mailed overnight to the Rutgers lab, that could produce a result within 48 to 72 hours. It costs $150 out of pocket.

“When sports leagues started calling us,” Feldman said, “they said almost universally, ‘We have athletes who want to come back to practice and we need a plan that could safely bring them back.’”

While Feldman said sports leagues make up a small percentage of his company’s testing clientele, he said Vault had supplied tests to the PGA, L.P.G.A., M.L.S., and N.H.L., as well as a small portion of the N.B.A.’s testing operation. A M.L.S. spokesman said Vault had provided testing for 13 teams during training, while BioReference Laboratories would do so at the league’s restricted-site tournament that recently began outside Orlando, Fla.

An N.H.L. spokesman said the league wasn’t prepared to disclose its testing company, and the N.B.A. did not respond to a request seeking comment.

The PGA Tour, which had restarted competition in mid-June in Texas, was the first professional sports organization to hire Vault, Feldman said. Levinson, the tour executive, said the saliva test was basically used to approve travel: Golfers and caddies take the test before heading to an event, and then once again on the Saturday of a tournament to determine if they can board the tour’s charter plane on Monday to the next event.

But the tour needed a speedier solution for on-site testing to monitor individuals’ health during the events without clogging up local labs. For that, Levinson said, they enlisted Sanford Health, a South Dakota organization that was already a title sponsor of a PGA Tour Champions event.

Sanford Health converted leftover medical trucks into three mobile laboratories, Levinson said, which can return results from the nasopharyngeal swab test in less than two hours.

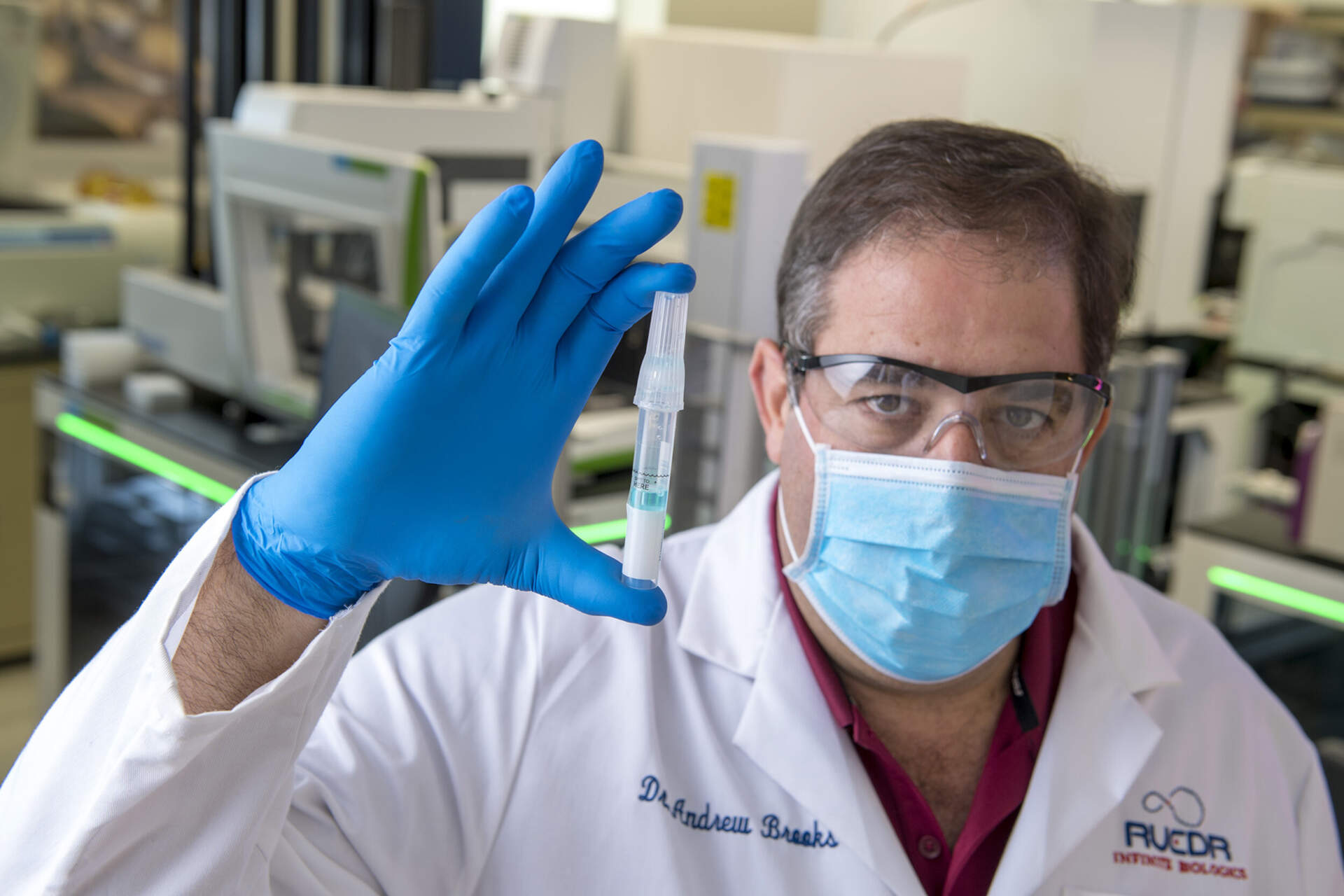

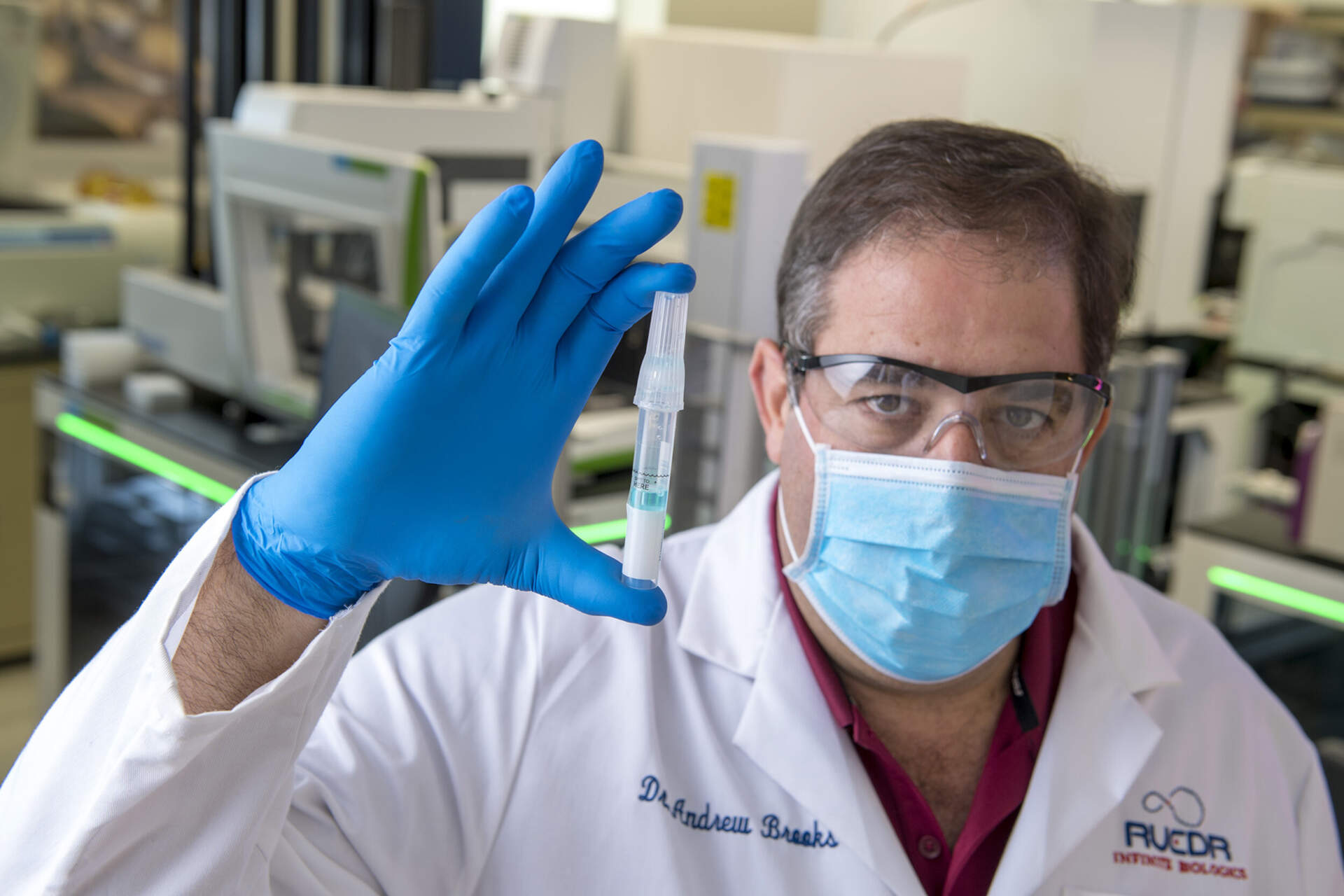

Dr. Andrew Brooks, Chief Operating Officer at RUCDR Infinite Biologics is processing Spectrum saliva collection devices which enable RUCDR to screen a much broader population without putting health care professionals at risk. Self-collection of saliva is vital in reducing the spread of COVID-19 as well as preserving personal protective equipment necessary for safe patient care.

Seeing an Opportunity

Navigating the rapidly evolving world of coronavirus testing has been far from a simple task for professional sports leagues. They have had to weigh the efficacy and speed of various tests and companies, all while trying to ensure they would not be taking away resources from those who needed them more.

“It was incredibly complicated,” said Andy Levinson, the PGA Tour’s senior vice president of tournament administration.

When leagues began exploring their options — Levinson said the tour consulted laboratory directors and its own medical advisers — saliva-based tests emerged as a popular choice. They could be done almost anywhere, with minimal assistance from a medical professional and without much personal protective equipment, and some studies found saliva was a reliable alternative to the more-common nasopharyngeal swabs.

Another benefit: Spitting in a tube is much less painful than a swab shoved deep into the nasal cavity.

“We call it the brain tickler,” said Jason Feldman, the chief executive of Vault Health. Feldman’s company is now a linchpin for several leagues’ coronavirus testing operations. Before the pandemic, it was part of a growing wave of telehealth companies, connecting patients with doctors via video calls, and facilitating shipments of treatments through the mail.

When the pandemic hit the U.S., Feldman, like many business owners, feared the potential economic effects on his company. But then he realized he was sitting on a wealth of resources that would be useful amid the crisis: He had a relationship with both the Rutgers lab, known as RUCDR Infinite Biologics, and Spectrum Solutions for other products, and a virtual consultation platform that would provide a safe way to talk to patients.

Vault Health devised an at-home saliva testing package, which is supervised via a Zoom video call and mailed overnight to the Rutgers lab, that could produce a result within 48 to 72 hours. It costs $150 out of pocket.

“When sports leagues started calling us,” Feldman said, “they said almost universally, ‘We have athletes who want to come back to practice and we need a plan that could safely bring them back.’”

While Feldman said sports leagues make up a small percentage of his company’s testing clientele, he said Vault had supplied tests to the PGA, L.P.G.A., M.L.S., and N.H.L., as well as a small portion of the N.B.A.’s testing operation. A M.L.S. spokesman said Vault had provided testing for 13 teams during training, while BioReference Laboratories would do so at the league’s restricted-site tournament that recently began outside Orlando, Fla.

An N.H.L. spokesman said the league wasn’t prepared to disclose its testing company, and the N.B.A. did not respond to a request seeking comment.

The PGA Tour, which had restarted competition in mid-June in Texas, was the first professional sports organization to hire Vault, Feldman said. Levinson, the tour executive, said the saliva test was basically used to approve travel: Golfers and caddies take the test before heading to an event, and then once again on the Saturday of a tournament to determine if they can board the tour’s charter plane on Monday to the next event.

But the tour needed a speedier solution for on-site testing to monitor individuals’ health during the events without clogging up local labs. For that, Levinson said, they enlisted Sanford Health, a South Dakota organization that was already a title sponsor of a PGA Tour Champions event.

Sanford Health converted leftover medical trucks into three mobile laboratories, Levinson said, which can return results from the nasopharyngeal swab test in less than two hours.

Dr. Andrew Brooks, Chief Operating Officer at RUCDR Infinite Biologics is processing Spectrum saliva collection devices which enable RUCDR to screen a much broader population without putting health care professionals at risk. Self-collection of saliva is vital in reducing the spread of COVID-19 as well as preserving personal protective equipment necessary for safe patient care.

A Sudden Demand

Phillips, the Spectrum Solutions executive, said that he had talked with nearly all of the professional sports leagues in the U.S., including the National Women’s Soccer League and U.F.C., because many compare notes.

“It was just a cascading effect,” he said. “One called me then another and another.” M.L.B., he said, came to him in April and was expecting to use 275,000 of his kits by the end of the year.

To meet the sudden demand, Phillips said recently that Spectrum Solutions’ factory was working around the clock to make 3.5 million saliva test kits this month. He hoped to double that number, and his staff, to about 500, by August.

Thanks to automation, Dr. Andy Brooks, the chief operating officer of RUCDR, said his lab in Piscataway, N.J., could handle 50,000 tests per day, with more room to grow. He said they had five $2 million modules — robots, essentially — each handling about 10,000 tests, and each requiring about 25 people to run.

“We are the McDonald’s of molecular lab services,” he said. “We build a process and make it efficient.”

Throughout the pandemic, public health experts have questioned whether sports leagues were jumping to the front of the line for tests at the expense of the general population. Phillips said his company has donated kits to emergency medical workers in Utah and sold them to whoever wants them, trying to fill the void created by what he called the government’s uneven response to the pandemic.

“There’s a shortage of product, but there’s an even bigger shortage of authorized labs,” he said, alluding to the F.D.A.’s backlog in emergency-use authorizations for labs that could potentially handle such tests. “If we made 100 million, we can sell 100 million.”

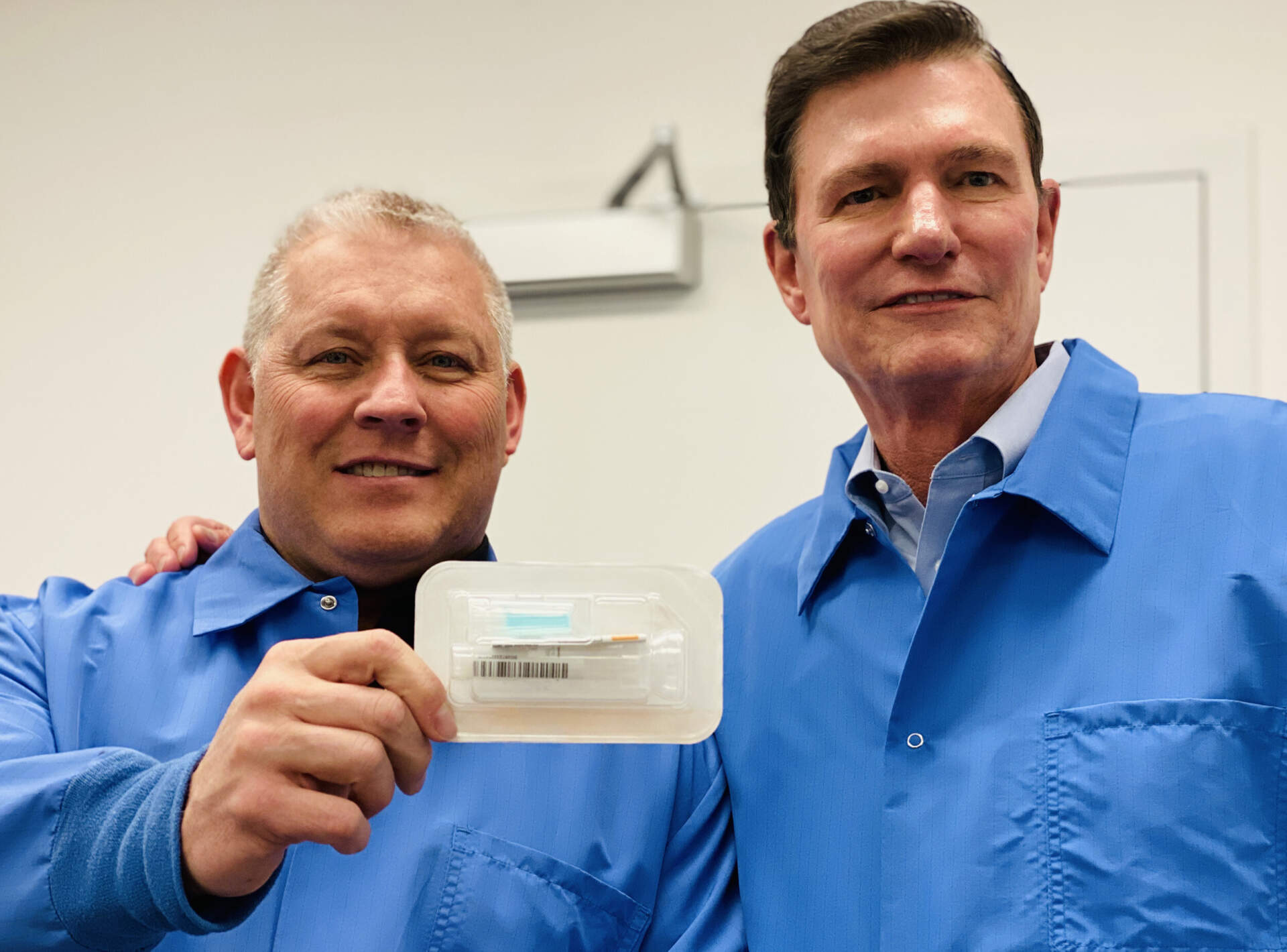

Bill Phillips, COO of Spectrum Solutions, left, and Stephen Fanning, CEO of Spectrum Solutions holding SDNA-1000 saliva collection kit. ©Spectrum Solutions™ | Photo Credit: Leslie Titus Bryant

A Sudden Demand

Phillips, the Spectrum Solutions executive, said that he had talked with nearly all of the professional sports leagues in the U.S., including the National Women’s Soccer League and U.F.C., because many compare notes.

“It was just a cascading effect,” he said. “One called me then another and another.” M.L.B., he said, came to him in April and was expecting to use 275,000 of his kits by the end of the year.

To meet the sudden demand, Phillips said recently that Spectrum Solutions’ factory was working around the clock to make 3.5 million saliva test kits this month. He hoped to double that number, and his staff, to about 500, by August.

Thanks to automation, Dr. Andy Brooks, the chief operating officer of RUCDR, said his lab in Piscataway, N.J., could handle 50,000 tests per day, with more room to grow. He said they had five $2 million modules — robots, essentially — each handling about 10,000 tests, and each requiring about 25 people to run.

“We are the McDonald’s of molecular lab services,” he said. “We build a process and make it efficient.”

Throughout the pandemic, public health experts have questioned whether sports leagues were jumping to the front of the line for tests at the expense of the general population. Phillips said his company has donated kits to emergency medical workers in Utah and sold them to whoever wants them, trying to fill the void created by what he called the government’s uneven response to the pandemic.

“There’s a shortage of product, but there’s an even bigger shortage of authorized labs,” he said, alluding to the F.D.A.’s backlog in emergency-use authorizations for labs that could potentially handle such tests. “If we made 100 million, we can sell 100 million.”

Bill Phillips, COO of Spectrum Solutions, left, and Stephen Fanning, CEO of Spectrum Solutions holding SDNA-1000 saliva collection kit. ©Spectrum Solutions™ | Photo Credit: Leslie Titus Bryant

‘We Didn’t Want to Sit Idle’

Unlike other leagues, M.L.B. opted to use SMRTL, the anti-doping lab in Utah, to conduct its testing. Dr. Eichner said SMRTL followed the Rutgers lab’s model for its saliva testing.

Why SMRTL, a nonprofit, morphed from an anti-doping testing and research lab into one focusing mostly on coronavirus testing has to do with Dr. Eichner’s background: He has a P.h.D. in viral immunology from the Australian National University.

And as the coronavirus raged through the U.S. in March, he foresaw that the demand for antidoping testing would decrease as sports stopped, and the need for coronavirus testing would skyrocket.

“We had a lot of really good, smart scientists, a lot of good instruments and we didn’t want to sit idle,” he said, adding later, “I knew we could do this test.”

As Dr. Eichner explored ways to use SMRTL to add to the country’s testing capacity, M.L.B. was looking for return-to-play testing. The league paid to convert SMRTL into a coronavirus testing site, Commissioner Rob Manfred has said — and luckily for SMRTL, it had moved to a new facility in early March that is three times as large as its previous site.

To test the saliva coronavirus samples, the lab also needed to clear several federal hurdles. Dr. Eichner said SMRTL — used to dealing with anonymous athlete samples — boosted its secure network to meet federal medical privacy laws for handling patient information. While SMRTL is awaiting formal authorization from the F.D.A. on its application for an emergency-use authorization, Dr. Eichner said they were allowed to operate in the meantime.

But M.L.B.’s testing got off to an uneven start as teams began formal training again this month. At least six M.L.B. teams, including last year’s World Series participants, the Washington Nationals and the Houston Astros, canceled or postponed workouts during the first week because of delays in receiving test results. Test collectors also reportedly failed to show up in some instances.

M.L.B. said “unforeseen delays” in shipping over the July 4 holiday weekend had affected only a limited number of results and that it had since addressed the testing issues.

Before the delays became public last weekend, Dr. Eichner explained that SMRTL had promised M.L.B. a 24-hour turnaround on test results from the moment they receive the saliva shipments. “We’ve got no control on collection or shipping of the sample,” he said.

In the wake of those hiccups, an M.L.B. spokesman said in a statement on Friday that a portion of its nonplayer tests were expected to be handled by the Rutgers lab, and not solely SMRTL as originally planned. The spokesman said the decision had nothing to do with SMRTL’s capacity to handle the necessary testing.

With M.L.B. testing its players and key personnel at least twice a week, Dr. Eichner said SMRTL moved from working five days a week to every day, added at least five new people and can now process 2,000-2,500 samples a day. There are split shifts: an early morning and later start to get the results out by the evening.

“All that bureaucratic stuff was the hard stuff,” he said. “The actual science was really easy for us.”

‘We Didn’t Want to Sit Idle’

Unlike other leagues, M.L.B. opted to use SMRTL, the anti-doping lab in Utah, to conduct its testing. Dr. Eichner said SMRTL followed the Rutgers lab’s model for its saliva testing.

Why SMRTL, a nonprofit, morphed from an anti-doping testing and research lab into one focusing mostly on coronavirus testing has to do with Dr. Eichner’s background: He has a P.h.D. in viral immunology from the Australian National University.

And as the coronavirus raged through the U.S. in March, he foresaw that the demand for antidoping testing would decrease as sports stopped, and the need for coronavirus testing would skyrocket.

“We had a lot of really good, smart scientists, a lot of good instruments and we didn’t want to sit idle,” he said, adding later, “I knew we could do this test.”

As Dr. Eichner explored ways to use SMRTL to add to the country’s testing capacity, M.L.B. was looking for return-to-play testing. The league paid to convert SMRTL into a coronavirus testing site, Commissioner Rob Manfred has said — and luckily for SMRTL, it had moved to a new facility in early March that is three times as large as its previous site.

To test the saliva coronavirus samples, the lab also needed to clear several federal hurdles. Dr. Eichner said SMRTL — used to dealing with anonymous athlete samples — boosted its secure network to meet federal medical privacy laws for handling patient information. While SMRTL is awaiting formal authorization from the F.D.A. on its application for an emergency-use authorization, Dr. Eichner said they were allowed to operate in the meantime.

But M.L.B.’s testing got off to an uneven start as teams began formal training again this month. At least six M.L.B. teams, including last year’s World Series participants, the Washington Nationals and the Houston Astros, canceled or postponed workouts during the first week because of delays in receiving test results. Test collectors also reportedly failed to show up in some instances.

M.L.B. said “unforeseen delays” in shipping over the July 4 holiday weekend had affected only a limited number of results and that it had since addressed the testing issues.

Before the delays became public last weekend, Dr. Eichner explained that SMRTL had promised M.L.B. a 24-hour turnaround on test results from the moment they receive the saliva shipments. “We’ve got no control on collection or shipping of the sample,” he said.

In the wake of those hiccups, an M.L.B. spokesman said in a statement on Friday that a portion of its nonplayer tests were expected to be handled by the Rutgers lab, and not solely SMRTL as originally planned. The spokesman said the decision had nothing to do with SMRTL’s capacity to handle the necessary testing.

With M.L.B. testing its players and key personnel at least twice a week, Dr. Eichner said SMRTL moved from working five days a week to every day, added at least five new people and can now process 2,000-2,500 samples a day. There are split shifts: an early morning and later start to get the results out by the evening.

“All that bureaucratic stuff was the hard stuff,” he said. “The actual science was really easy for us.”

Bringing Baseball Back!

How you collect saliva makes a big difference

Increase workplace safety and build team confidence with simple and safe repeat testing programs supporting 100% accurate early detection and easy direct-to-user at-home options. Just ask Major League Baseball. See how our saliva collection system is credited for “bringing baseball back” and making Salt Lake “the league’s most important city”.

™/© 2020 MLB

Bringing Baseball Back!

How you collect saliva makes a big difference

Increase workplace safety and build team confidence with simple and safe repeat testing programs supporting 100% accurate early detection and easy direct-to-user at-home options. Just ask the Major League Baseball. See how our saliva collection system is credited for “bringing baseball back” and making Salt Lake “the league’s most important city”.

™/© 2020 MLB

About Spectrum Solutions®

Headquartered in Salt Lake City, Utah, Spectrum Solutions is dedicated to empowering complete wellness and bridging the gap between science and innovative healthcare solutions. Our stand-alone and fully integrated test-to-treat solutions support molecular diagnostics and DTC testing applications, advancing product development and accelerating go-to-market applications. Our single-source, end-to-end capabilities include a CAP/CLIA accredited molecular diagnostic laboratory, onsite compounding pharmacy, medical and non-medical product development, manufacturing, and fulfillment.

![]()

Spectrum Corporate Spokesman

Spectrum Corporate Spokesman

Leslie Titus Bryant

Head of Marketing & Brand

admin@spectrumsolution.com

Media Contact

Media Contact

Tim Rush, Springboard5

801-208-1100

tim.rush@springboard5.com

About Spectrum Solutions®

Headquartered in Salt Lake City, Utah, Spectrum Solutions is dedicated to empowering complete wellness and bridging the gap between science and innovative healthcare solutions. Our stand-alone and fully integrated test-to-treat solutions support molecular diagnostics and DTC testing applications, advancing product development and accelerating go-to-market applications. Our single-source, end-to-end capabilities include a CAP/CLIA accredited molecular diagnostic laboratory, onsite compounding pharmacy, medical and non-medical product development, manufacturing, and fulfillment.

![]()

Spectrum Corporate Spokesman

Spectrum Corporate Spokesman

Leslie Titus Bryant

Head of Marketing & Brand

admin@spectrumsolution.com

Media Contact

Media Contact

Tim Rush, Springboard5

801-208-1100

tim.rush@springboard5.com

Spectrum

in the News

Spectrum

in the News

Noninvasive

Saliva Diagnostics

This changes everything!

Saliva analysis looks at the cellular level, the biologically active compounds, making it a true representative of what is clinically relevant. Engineered to lead the saliva collection industry, the BioMAX™ delivers the safest and most robust biosample for the earliest detection and diagnosis of disease and infection.

Since 2020 and the COVID-19 pandemic, Spectrum’s saliva collection system not only introduced, it continues to expand the molecular diagnostics industry and its understanding of the opportunities saliva offers patients, providers, and laboratories.

Noninvasive

Saliva Diagnostics

This changes everything!

Saliva analysis looks at the cellular level, the biologically active compounds, making it a true representative of what is clinically relevant. Engineered to lead the saliva collection industry, the BioMAX™ delivers the safest and most robust biosample for the earliest detection and diagnosis of disease and infection.

Since 2020 and the COVID-19 pandemic, Spectrum’s saliva collection system not only introduced, it continues to expand the molecular diagnostics industry and its understanding of the opportunities saliva offers patients, providers, and laboratories.

Outside-of-the-Box Thinking, Inside-of-the-Box Innovation

Anywhere from customized testing solutions to new medical science product innovations–we’re here to help.