WALL STREET JOURNAL:

THE NEW YORK TIMES: Just Spit and Wait – New Coronavirus Test Offers Advantage

By Ben Cohen, Louise Radnofsky and Brianna Abbott

Published: May 1, 2020

Published: May 1, 2020

Swabs or spit?

That was the question Anne Wyllie and a team of Yale University scientists set out to answer when they dropped everything they were doing last month and shifted their research focus to studying the new coronavirus.

They soon made an important finding: spitting into a cup appears to be as effective at detecting this virus as sticking a swab into your nose.

And that could have even more important implications for the U.S.’s ability to test large numbers of people for the virus.

Nasopharyngeal swabs are currently the gold standard of specimen collection for the virus. But they’re also in short supply, require health-care professionals wearing protective equipment to administer them and feel like they poke the patient’s brain. All of that contributes to a testing bottleneck that stands in the way of restarting the American economy.

“We know the hurdles of collecting nasopharyngeal swabs and said there’s got to be a better way,” said Andrew Brooks, chief operating officer and director of technology development at Rutgers University’s RUCDR Infinite Biologics, who is leading the charge on saliva testing across the country.

Collecting and analyzing a patient’s spit was one such possibility. But a big, unanswered question was if there would be enough virus in the saliva to easily detect. The sensitivity of the test with nasopharyngeal swabs is sometimes lacking, partially because it can be difficult to take a good sample, and less-invasive nasal swabs taken from a person’s nose tend to have fewer copies of the virus.

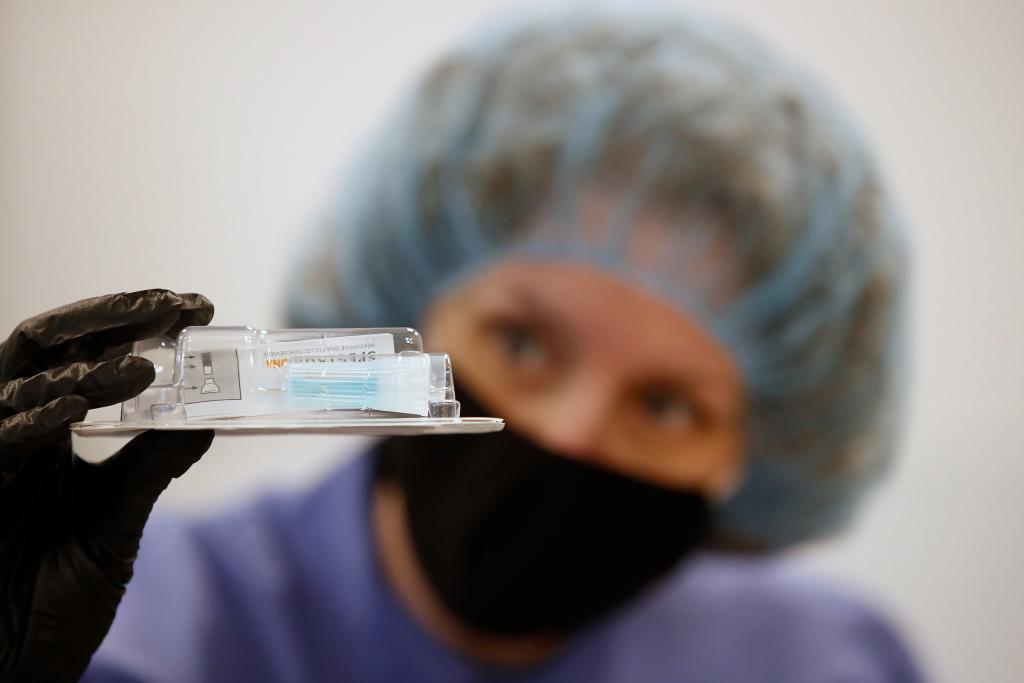

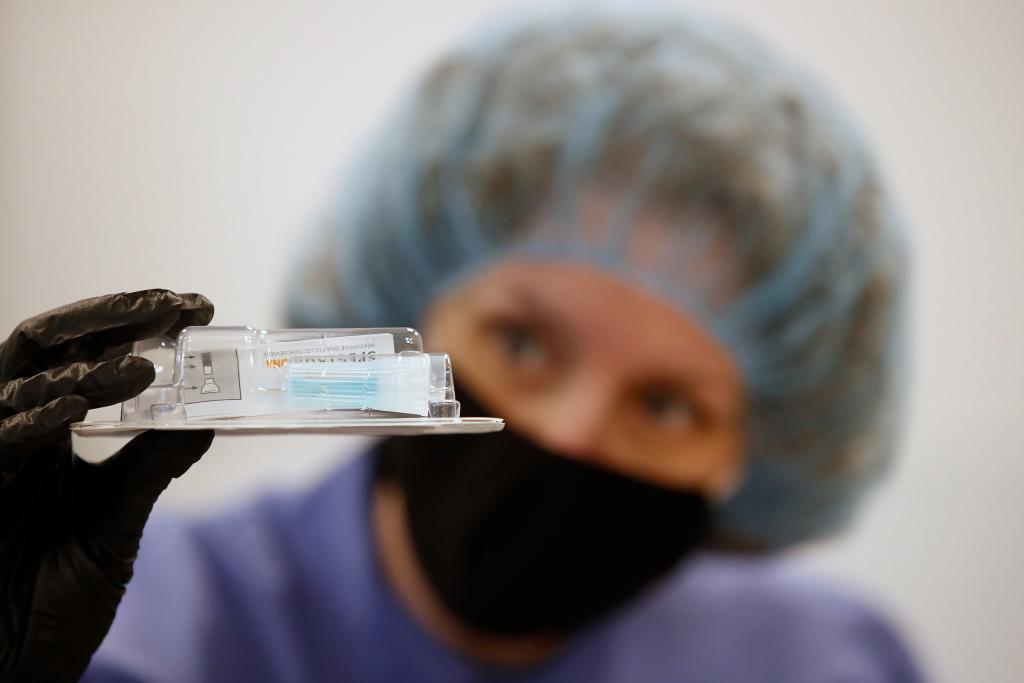

© Spectrum Solutions™ COVID-19 SDNA-1000 Saliva Collection Testing Kit | Bloomberg News

Swabs or spit?

That was the question Anne Wyllie and a team of Yale University scientists set out to answer when they dropped everything they were doing last month and shifted their research focus to studying the new coronavirus.

They soon made an important finding: spitting into a cup appears to be as effective at detecting this virus as sticking a swab into your nose.

And that could have even more important implications for the U.S.’s ability to test large numbers of people for the virus.

Nasopharyngeal swabs are currently the gold standard of specimen collection for the virus. But they’re also in short supply, require health-care professionals wearing protective equipment to administer them and feel like they poke the patient’s brain. All of that contributes to a testing bottleneck that stands in the way of restarting the American economy.

“We know the hurdles of collecting nasopharyngeal swabs and said there’s got to be a better way,” said Andrew Brooks, chief operating officer and director of technology development at Rutgers University’s RUCDR Infinite Biologics, who is leading the charge on saliva testing across the country.

Collecting and analyzing a patient’s spit was one such possibility. But a big, unanswered question was if there would be enough virus in the saliva to easily detect. The sensitivity of the test with nasopharyngeal swabs is sometimes lacking, partially because it can be difficult to take a good sample, and less-invasive nasal swabs taken from a person’s nose tend to have fewer copies of the virus.

© Spectrum Solutions™ COVID-19 SDNA-1000 Saliva Collection Testing Kit | Bloomberg News

It doesn’t have to be better than, as long as it’s ‘as good as’.

When Dr. Wyllie and the Yale team compared samples of saliva with nasopharyngeal swabs, however, the simpler, painless method proved to be successful, according to the report that the 50 researchers posted last week on the preprint server medRxiv.

“It doesn’t have to be ‘better than,’” Dr. Wyllie said. “As long as it’s ‘as good as.’”

But the samples of saliva were not merely as good as the swabs in their small study. They were apparently better. The diagnostic test for both was the same—aside from scouring a different type of patient sample for chunks of the virus’s genetic code.

While their work is preliminary and still awaits peer review and publication, the idea of sampling spit is already spreading across the country, and at least two states are using saliva in addition to swabs.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted the first emergency use authorization for saliva collection to Dr. Brooks’s team at Rutgers on April 13—before the Yale report went up online.

To secure that authorization, the team and their collaborators collected both saliva and either a nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swab from 60 patients. The results from the saliva and swab samples matched for all 60.

This proof of concept about the power of saliva comes at a time when testing has never been so essential.

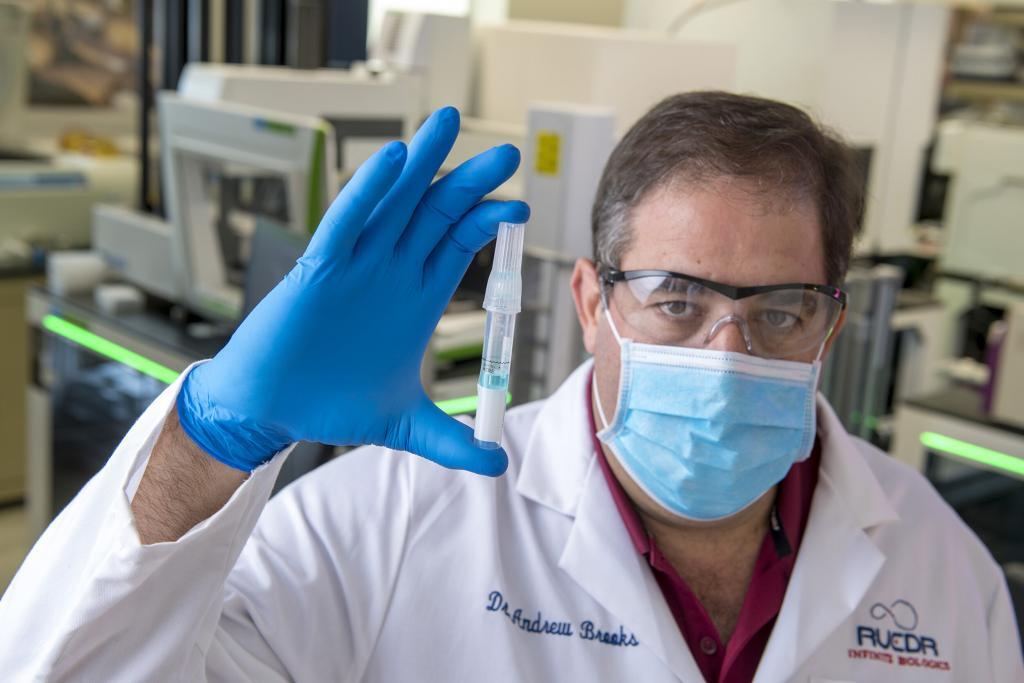

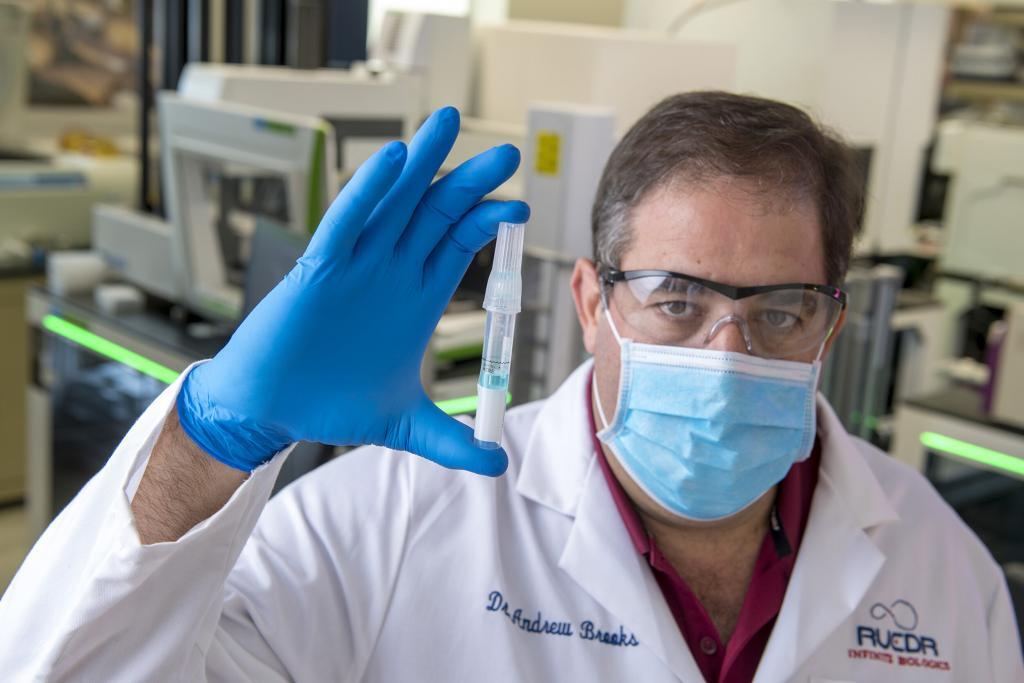

Dr. Andrew Brooks, Chief Operating Officer at RUCDR Infinite Biologics is processing Spectrum saliva collection devices.

When Dr. Wyllie and the Yale team compared samples of saliva with nasopharyngeal swabs, however, the simpler, painless method proved to be successful, according to the report that the 50 researchers posted last week on the preprint server medRxiv.

“It doesn’t have to be ‘better than,’” Dr. Wyllie said. “As long as it’s ‘as good as.’”

But the samples of saliva were not merely as good as the swabs in their small study. They were apparently better. The diagnostic test for both was the same—aside from scouring a different type of patient sample for chunks of the virus’s genetic code.

While their work is preliminary and still awaits peer review and publication, the idea of sampling spit is already spreading across the country, and at least two states are using saliva in addition to swabs.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted the first emergency use authorization for saliva collection to Dr. Brooks’s team at Rutgers on April 13—before the Yale report went up online.

To secure that authorization, the team and their collaborators collected both saliva and either a nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swab from 60 patients. The results from the saliva and swab samples matched for all 60.

This proof of concept about the power of saliva comes at a time when testing has never been so essential.

Dr. Andrew Brooks, Chief Operating Officer at RUCDR Infinite Biologics is processing Spectrum saliva collection devices.

A saliva-based test could be game-changing

A non-invasive, self-administered, highly effective spit test could help mass testing become a closer reality. It cuts the demand for supplies such as swabs, preserves the labor of health-care workers, reduces the need for personal protective equipment, alleviates some pressure on global supply chains and makes the test more appealing than your average root canal surgery.

A saliva-based test could be “game-changing” for those reasons, said Rochelle Walensky, the chief of infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Now the labs capable of analyzing those saliva tests are moving quickly to adapt. The lab at Rutgers was accustomed to processing DNA genetic tests—people spitting into tubes. “I had never done a viral test in my life maybe six weeks ago,” said Jay Tischfield, a distinguished professor of genetics at Rutgers.

But the lab was repurposed almost overnight to handle 10,000 coronavirus saliva tests per day, including samples from drive-through sites, and Dr. Tischfield said they recently paid $2 million to clone their equipment and double the lab’s output. The Rutgers test also includes a preservative that helps keep the sample stable between collection and analysis.

The Yale paper helps support that approach. To determine whether spit tests could detect the coronavirus with the same accuracy as the uncomfortable but historically reliable nasopharyngeal swabs, Dr. Wyllie and her team collected samples from 44 patients at Yale New Haven Hospital who had already tested positive and 98 asymptomatic health-care workers. The size of their study has since increased to 89 and 178, respectively.

They found the spit tests to be more sensitive to the virus with more consistent results. They also detected the virus in the saliva of two health-care workers who had tested negative using the nasopharyngeal swabs.

It wasn’t long before the Yale study was the subject of enthusiastic tweets from researchers and luminaries in the coronavirus response, including Scott Gottlieb, the former FDA commissioner who is advising the U.S. government.

© Spectrum Solutions™ COVID-19 SDNA-1000 Saliva Collection Testing Kit | Bloomberg News/George Frey

A non-invasive, self-administered, highly effective spit test could help mass testing become a closer reality. It cuts the demand for supplies such as swabs, preserves the labor of health-care workers, reduces the need for personal protective equipment, alleviates some pressure on global supply chains and makes the test more appealing than your average root canal surgery.

A saliva-based test could be “game-changing” for those reasons, said Rochelle Walensky, the chief of infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Now the labs capable of analyzing those saliva tests are moving quickly to adapt. The lab at Rutgers was accustomed to processing DNA genetic tests—people spitting into tubes. “I had never done a viral test in my life maybe six weeks ago,” said Jay Tischfield, a distinguished professor of genetics at Rutgers.

But the lab was repurposed almost overnight to handle 10,000 coronavirus saliva tests per day, including samples from drive-through sites, and Dr. Tischfield said they recently paid $2 million to clone their equipment and double the lab’s output. The Rutgers test also includes a preservative that helps keep the sample stable between collection and analysis.

The Yale paper helps support that approach. To determine whether spit tests could detect the coronavirus with the same accuracy as the uncomfortable but historically reliable nasopharyngeal swabs, Dr. Wyllie and her team collected samples from 44 patients at Yale New Haven Hospital who had already tested positive and 98 asymptomatic health-care workers. The size of their study has since increased to 89 and 178, respectively.

They found the spit tests to be more sensitive to the virus with more consistent results. They also detected the virus in the saliva of two health-care workers who had tested negative using the nasopharyngeal swabs.

It wasn’t long before the Yale study was the subject of enthusiastic tweets from researchers and luminaries in the coronavirus response, including Scott Gottlieb, the former FDA commissioner who is advising the U.S. government.

© Spectrum Solutions™ COVID-19 SDNA-1000 Saliva Collection Testing Kit | Bloomberg News/George Frey

Spit tests to be more sensitive to the virus with more consistent results

Paul Romer, a Nobel Prize-winning economist, believes that significantly boosting the number of tests is the only way out of the economic and health crises. A simpler collection device that uses spit instead of swabs would make it easier to supersize the nation’s testing capacity, he said in an interview.

The Yale research is supported by similar findings in Australia, Thailand and California in addition to the Rutgers test. It’s an exhilarating time for scientists who find themselves collaborating with strangers around the world through manuscripts and Twitter exchanges as the notoriously laborious process of academic publishing has accelerated to keep pace with the virus.

“The more that we share and help each other out, it’s going to increase all of our capacities to respond to this,” Dr. Wyllie said. “This is not a time to be squirreling away your own secret research methods and working behind the scenes.”

Dr. Wyllie’s work helped support the testing strategy already underway at Rutgers, Dr. Tischfield said. The New Jersey model has been adopted by Oklahoma, where state officials announced plans this week to use saliva tests instead of swabs on more than 40,000 residents and staff in long-term care facilities.

The Rutgers researchers have since fielded calls from doctors and officials across the country, Dr. Brooks said. Other hospital systems have also started comparing swab and saliva samples from patients to see if they get similar results. The Wadsworth Center, the public health laboratory in New York, has been validating saliva paired with nasal swabs and expects to be able to deploy it in the field “very soon,” according to a statement from the New York State Department of Health.

Doctor takes a swab from his nose to test for the coronavirus | PHOTO: ANUSHREE FADNAVIS/REUTERS

Paul Romer, a Nobel Prize-winning economist, believes that significantly boosting the number of tests is the only way out of the economic and health crises. A simpler collection device that uses spit instead of swabs would make it easier to supersize the nation’s testing capacity, he said in an interview.

The Yale research is supported by similar findings in Australia, Thailand and California in addition to the Rutgers test. It’s an exhilarating time for scientists who find themselves collaborating with strangers around the world through manuscripts and Twitter exchanges as the notoriously laborious process of academic publishing has accelerated to keep pace with the virus.

“The more that we share and help each other out, it’s going to increase all of our capacities to respond to this,” Dr. Wyllie said. “This is not a time to be squirreling away your own secret research methods and working behind the scenes.”

Dr. Wyllie’s work helped support the testing strategy already underway at Rutgers, Dr. Tischfield said. The New Jersey model has been adopted by Oklahoma, where state officials announced plans this week to use saliva tests instead of swabs on more than 40,000 residents and staff in long-term care facilities.

The Rutgers researchers have since fielded calls from doctors and officials across the country, Dr. Brooks said. Other hospital systems have also started comparing swab and saliva samples from patients to see if they get similar results. The Wadsworth Center, the public health laboratory in New York, has been validating saliva paired with nasal swabs and expects to be able to deploy it in the field “very soon,” according to a statement from the New York State Department of Health.

Doctor takes a swab from his nose to test for the coronavirus | PHOTO: ANUSHREE FADNAVIS/REUTERS

Study proves saliva superior for pneumococcal carriage detection

Infectious disease experts say that some of the early results are promising but likely need more data and bigger studies to back them up.

“That was encouraging,” Daniel Kuritzkes, the chief of the division of infectious disease at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said of the Yale preprint. “Saliva by itself won’t solve all the problems. It does solve some important bottlenecks.”

Dr. Wyllie, who is from New Zealand and moved to the Netherlands for graduate school, concentrated on this line of research when she came across a study published in the 1930s and learned that saliva had once been used for pneumococcal carriage detection. Dr. Wyllie decided to find out whether that was still possible. Her promising results on children led to comparing saliva with nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs in adults and the elderly—and the spit tests were superior.

She designed a similar experiment in New Haven, Conn., to build on that research. It was supposed to begin in early March.

“We work with older adults,” Dr. Wyllie said. “How could we risk sending anyone into their homes when we knew they were vulnerable?”

It appeared that Dr. Wyllie had picked quite possibly the worst time in a century to be a pneumococcologist. But it turned out her timing couldn’t have been any better. Dr. Wyllie turned her attention to SARS-CoV-2—and the Yale report was posted online less than a month later.

Infectious disease experts say that some of the early results are promising but likely need more data and bigger studies to back them up.

“That was encouraging,” Daniel Kuritzkes, the chief of the division of infectious disease at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said of the Yale preprint. “Saliva by itself won’t solve all the problems. It does solve some important bottlenecks.”

Dr. Wyllie, who is from New Zealand and moved to the Netherlands for graduate school, concentrated on this line of research when she came across a study published in the 1930s and learned that saliva had once been used for pneumococcal carriage detection. Dr. Wyllie decided to find out whether that was still possible. Her promising results on children led to comparing saliva with nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs in adults and the elderly—and the spit tests were superior.

She designed a similar experiment in New Haven, Conn., to build on that research. It was supposed to begin in early March.

“We work with older adults,” Dr. Wyllie said. “How could we risk sending anyone into their homes when we knew they were vulnerable?”

It appeared that Dr. Wyllie had picked quite possibly the worst time in a century to be a pneumococcologist. But it turned out her timing couldn’t have been any better. Dr. Wyllie turned her attention to SARS-CoV-2—and the Yale report was posted online less than a month later.

Spectrum

in the News

Spectrum

in the News

Noninvasive

Saliva Diagnostics

This changes everything!

Saliva analysis looks at the cellular level, the biologically active compounds, making it a true representative of what is clinically relevant. Engineered to lead the saliva collection industry, the BioMAX™ delivers the safest and most robust biosample for the earliest detection and diagnosis of disease and infection.

Since 2020 and the COVID-19 pandemic, Spectrum’s saliva collection system not only introduced, it continues to expand the molecular diagnostics industry and its understanding of the opportunities saliva offers patients, providers, and laboratories.

Noninvasive

Saliva Diagnostics

This changes everything!

Saliva analysis looks at the cellular level, the biologically active compounds, making it a true representative of what is clinically relevant. Engineered to lead the saliva collection industry, the BioMAX™ delivers the safest and most robust biosample for the earliest detection and diagnosis of disease and infection.

Since 2020 and the COVID-19 pandemic, Spectrum’s saliva collection system not only introduced, it continues to expand the molecular diagnostics industry and its understanding of the opportunities saliva offers patients, providers, and laboratories.

Outside-of-the-Box Thinking, Inside-of-the-Box Innovation

Anywhere from customized testing solutions to new medical science product innovations–we’re here to help.